By / DAVID MERREFIELD

Attention private label manufacturers: Rejoice!

Lidl, the gigantic private label-driven discounter from Germany, has made it plain enough that it intends to establish a fleet of stores in America. Since it isn’t likely that many of its numerous own brands manufactured in Europe could be shipped to the U.S. in sufficient quantity, Lidl will have to establish new manufacturing and distribution supply arrangements in the U.S.

But before we break out the party hats, let’s take a look at a couple of key issues facing Lidl: — Most important, what are the odds that Lidl can successfully establish in the U.S. given the dismal record of failure in America established by so many other European food retailers.

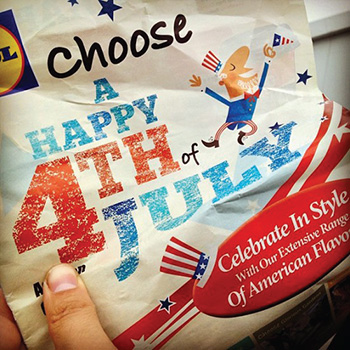

— Secondly, although Lidl offers a high proportion of private label product in many of its European operating arenas, can Lidl do the same in America?

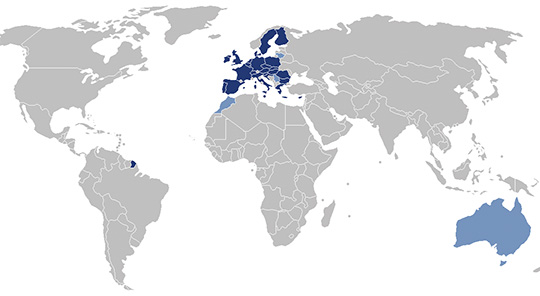

There’s no doubt Lidl can bring a lot of fire power to America. After all, its annual revenues are estimated at $US 80 Billion. It has about 10,000 stores in some 20 European countries. By any measure, it’s the largest pan-European food retailer of all.

Lidl Dispatches an Exploration Team >>

Lidl Dispatches an Exploration Team >>

Lidl’s plans for America remain a little amorphous, but what’s known is that Lidl has dispatched a team of explorers to America to scout out a site for a U.S. headquarters and distribution center, plus maybe 100 store sites for a blast of initial openings. It’s thought that doors to the stores may be flung open in less than two years. Further, the plan is that the initial number of stores may be multiplied several times over before too long.

To most observers, the fact that Lidl’s thinking about America has progressed this far is a sure indication that it will really happen. Several years ago, Lidl considered and rejected a leap to the U.S. or Canada.

where to locate stores, namely in the populous northeastern states, and perhaps further down the East Coast. Lidl’s deep discount, small format stores would be a good fit for the East, probably better than anywhere else in the country. That owes to population density and the lack of many other deep-discount stores in the region.

Nevertheless, the failure of several of its fellow European operators as they tried to break into the American market has to give pause.

From Tesco >>

Most spectacularly, Tesco of the U.K. failed in the most costly way imaginable after opening numerous small-format Fresh & Easy stores in the Southwest starting in 2007. Tesco started by establishing a distribution center and a fresh-product production center before opening a single store. It eventually opened 200 stores, but chalked up only losses of more than $3 billion in startup and operating costs.

Fresh & Easy has filed for bankruptcy, a process that is intended to facilitate the sale at auction of 150 stores plus the distribution assets to Yucaipa Cos., assuming no other bidder emerges. Tesco may pay roughly $200 million to Yucaipa to assume these obligations. In return, Yucaipa will grant an equity position of more than 30% to Tesco in whatever business it runs in the stores, which will probably be a revival of Wild Oats, a retail chain that was shuttered when it was sold to Whole Foods. A newly hired Yucaipa executive owns rights to the Wild Oats brand. Tesco will probably use bankruptcy to renounce some or all of 50 store leases not involved in the sale to Yucaipa. Some leases were for 20 years.

Similarly, Okey-Dokey Grocery abruptly closed its several stores in Florida, and a distribution center. Those stores were expected to form the nucleus of hundreds to follow. That retailer was the dream of Russian and Dutch investors.

And so it goes for European companies seeking to gain a foothold in America. Looking farther back, those that have failed include Carrefour, Auchan, Leclerc, Sainsbury, Marks & Spencer and 3 Guys.

But there are exceptions. Some level of success has been achieved in the U.S. by Ahold and Delhaize and — most tellingly — Aldi.

indeed, is the very chain that Lidl is modeled upon. Both the companies were founded in Germany, Aldi in 1962 and Lidl in 1973. Both use the limitedassortment, deep-discount approach. Both offer high stockkeeping unit counts in private label. Both pursued a strategy of robust expansion throughout western and eastern Europe.

Lidl is now a slightly larger company than is Aldi, as measured by revenue, operating countries and store counts. But they’re quite similar.

In 1976, Aldi made its leap to America by establishing a headquarters in the upper Midwest and quietly opening a few stores, many in near-failing shopping centers. The objective was to keep costs down to minimize the cost of failure, should that happen. It also caused the stealthy Aldi to be overlooked or underestimated by its competitors for years.

In 1976, Aldi made its leap to America by establishing a headquarters in the upper Midwest and quietly opening a few stores, many in near-failing shopping centers. The objective was to keep costs down to minimize the cost of failure, should that happen. It also caused the stealthy Aldi to be overlooked or underestimated by its competitors for years.

Now, Aldi has broken out. It has more than 1,000 stores in 30 states, many in the Midwest and some in the East. It now has a fleet of modern stores, many built by Aldi as freestanding units. It now has plans to expand quickly in Texas, Florida and California.

And so, it seems, Lidl plans to follow the path first trod by Aldi as it makes its foray into America.

This bodes well for Lidl because Aldi has done the heavy lifting of acquainting American shoppers with the deep-discount concept. Yet, it doesn’t have sufficient store density in the East to deny Lidl an avenue of approach.

One operational hazard for Lidl is its intention to establish a distribution center. To do that in advance of opening stores and testing them to see how they are accepted by consumers has the effect of increasing the cost of failure to astronomical levels, as many companies have discovered to their dismay.

An alternative would be to source product through a third-party wholesaler for a time until the format is proven. The downside is that Lidl would be hard pressed to sell product at price points well below those prevailing in its markets, as its format requires. But even if Lidl had to subsidize prices for a while, that would be a less costly alternative.

A Role for Private Label >>

Then, there’s the matter of private label. The lesson that has been learned repeatedly by food retailing startups, especially those with low-price positioning, is that it’s best to begin by selling a high percentage of branded product to cement the low-price advantage in consumers’ minds. Then, when they’re convinced, it’s possible to increase the private label range.

Retailers that have done that successfully include Walmart, Costco and Aldi. Aldi now offers nearly all private label.

So, should private label manufacturers indulge in a little rejoicing? Probably, but let’s give it some time.