By / Daniel Johansson, Associate Analyst, Planet Retail GmbH

Implications

* In current 3DP adoption the assumption of credit varies between retailers, FMCGs and technology vendors. Retailers will likely try to label services and products as their own if possible, but will face rising resistance as 3D printing gains a foothold in the consumer market.

* Retailers will have little involvement in the field once printers become common features in homes.

* 3D printers could become revolutionary tools in crowdsourcing private label products. However, potential may lie in the development and trial phase while mass-production could be kept for traditional manufacturing methods.

* Keeping retailer-exclusive (private-branded) design catalogues will likely not succeed. However, for products complementing other retailer-specific items (like spare parts) it could be viable.

* FMCG manufacturers should try to get their brands promoted in connection with 3DP and stores are perfect venues for this. Establishing themselves as materials and design suppliers early on is important if/when home printing breaks through.

Cake decorations are designed on a tablet and chocolate toppings then printed by a portable byFlow 3D-printer directly in the Albert Heijn store. © 3dp-expo.com

Almost every other week now, we see more and more retailers embracing the hot topic of 3D printing. To name just a few we’ve recently seen: Argos has stepped into 3D jewellery; Sam’s Club is adding 3D printers to 300 stores; Amazon is seeking to patent 3D printer trucks while Leroy Merlin is installing instore workshops with 3D printers available for use…

A few months ago, Dutch retailer Ahold launched the world’s first (as far as Planet Retail is aware) 3D printing (3DP) live trial for food in an Albert Heijn supermarket in Eindhoven. Shoppers can design their very own customised fully-edible cake decorations made out of chocolate and have these 3D printed instore. Even though the retailer claims the concept will be rolled out to 30 additional stores if successful, it’s obvious the installation was largely to create a buzz of publicity.

However, as the retailer seems to use its private label packaging for the cakes, it raises the question of who will stand as the responsible source of 3DP products in the future and the implications of the technology for private label. What will be the respective roles of retailers, FMCG manufacturers, technology vendors and designers in this paradigm shift for personalisation?

Disruptive, but temporary, technology for retailers >>

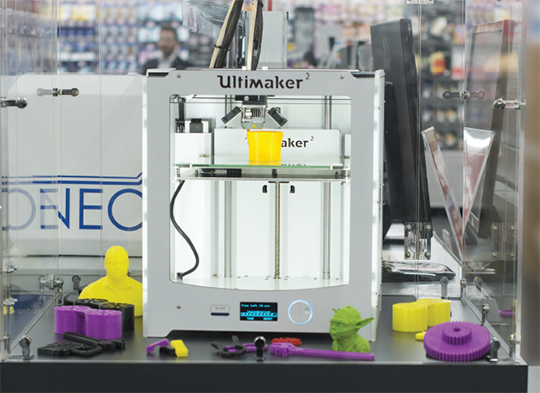

First, let’s begin with some background on what 3DP is and its advantages. 3DP enables the creation of a physical object from a three-dimensional digital plan. This is typically realised by overlaying successive thin layers of a material (usually a resin or plastic) following the contours described in a CAD template.

The clear advantages are immediacy (creating an item from scratch) and customisation – two major trends set to assume even greater importance in the near future. For retailers, 3DP means they could hypothetically offer vast product ranges without need to consider stocking or replenishment concerns. For more background, we recommend this Planet Retail article on the present status of the technology in retail.

The optimal scenario that would maximise 3DP’s advantages would be when consumers have their own machines in their homes and can print anything from a centralised open source blueprint directory. However, due to substantial hardware prices and the technology not yet being perfected, the product is in an early product cycle phase.

If and when 3DP becomes as mainstream as microwave ovens, retailers will likely have little involvement in the field other than selling the printers and requisite materials. The actual 3DP designs will – if not available as open source files – be developed and sold by producers or designer platforms.

Until this happens, retailers are the ideal venues for the initial trial phase of 3DP. There is great differentiation potential and an opportunity to create a special instore experience by offering the technology as a service. There are several examples of retailers already navigating these waters, including Target, Staples, Asda, Auchan and Amazon.

Who takes credit for the printed items?

Asda invites shoppers to undergo a 12-second 3D body scan and eventually obtain printed miniature figurines of themselves. Interestingly, this service is marketed under the slogan Asda 3DME – Memories you can hold on to. Once printed, the products are packaged in boxes bearing the same label. This is despite the fact that Artec’s 3D body-scanning technology and 3D Systems’ 3D printers are highly involved in the process.

In other words, Asda assumes credit for the result of the service as the responsible source. And why shouldn’t the retailer do so? After all, any retailer would like to be as closely associated as possible with such innovative technology to be perceived as cutting edge. In addition, vendors will likely be more than happy to gain the wide coverage a retailer can offer or, in some cases, might have to accept a co-branding or private label approach. This balance of power will likely shift once consolidation begins in the 3D printing market.

Other openings for retailers around using 3D printing instore might be to offer spare parts designed to directly fit their private label products – think immediately-available product repairs or upgrades. This could obviously also be extended to branded products, although that might throw up more complexities.

Amazon offers designs from third party actors on their site, some of which can be customised to a certain degree. Target offers its own designs through the 3D printing platform Shapeways, a kind of distribution method we feel will be unsustainable long term. However, neither use their own brand exclusively for the services or products. Auchan, likewise, allows the joint venture called Yoomake – formed of 3D customisation company Twikit and Belgian 3D printing service company i.materialise – take the limelight in its Lille pilot store.

The big question, of course, is what happens when consumers are product designers and want to print them instore and/or if retailers then want to reuse these designs for their own gain. The US office supplies retailer Staples offers the former option of inviting home designers to bring their own blueprints for printing instore. Despite the customer being the actual producer here, Staples markets itself as the service provider, much as does Asda. We will likely see retailers do this more often going forward.

So far we’ve gone through examples of retailer 3DP adoptions. But haven’t any FMCG producers adopted this technology? Well, one example is chocolate giant Hershey, which developed the CocoJet chocolate printer in collaboration with 3D Systems. Hershey’s idea is likely to introduce its own chocolate capsules and sell these accessories like butter (or chocolate) directly to private individuals, restaurants and retail outlets. Maybe in the future we could even see one FMCG printer and one retail 3D printer in the same store.

3D could take crowdsourcing to the next level >>

3D could take crowdsourcing to the next level >>

Another FMCG producer to invest in 3DP is Barilla. This leading pasta producer is currently working with TNO Eindhoven to build a custom 3D pasta printer. As part of this development it ran a contest for designers worldwide to contribute their own 3DP designs for a new type of pasta. As many as 216 contributions were received and three innovative designs named winners.

Kjeld van Bommel, project leader at TNO told The Guardian the goal is to be able to print 15-20 pieces of pasta in under two minutes. This time constraint is why traditional production methods will invariably be superior for mass production. However, if someone was to pick up on the new designs and, say, be willing to pay a premium for a spectacular pasta shape, be that instore, for printing at home or for restaurant service, then this could be a viable model.

Among the pasta Print Eat Contest winners was this bud-shaped pasta that blooms out into a rose when boiled. © Barilla.

With this example in mind, there is little to prevent retailers from running similar crowdsourcing initiatives for their private labels. The ideas could be printed instore, trialled and rated by shoppers and later mass-produced as a permanent part of the retailer’s assortment if deemed to have potential for success.

So what about retailers ‘private labelling’ their potentially endless aisles of 3D printable blueprints as created by their own designers alongside earlier shopper-sourced creations made on instore 3D printers? Will they maintain exclusive product catalogues under their own brand?

It’s unlikely that any such catalogue could better open source platforms like Makerbot’s Thingiverse when it comes to breadth. However, as in the case of Albert Heijn’s cake decorations it’s possible if the printed designs are particularly compatible with other items sold instore and, of course, approved for reuse by the designer. As stated earlier, spare parts for private label items are a further great application for 3D printed private label products. This opportunity would still exist long after people are printing their own bicycles and cars at home.

Something in it for everyone >>

So what does this all mean for retailers and FMCG manufacturers? Retailers will be lured by the differentiated store experience offered by 3D printing. However, if they promote the technology too zealously they might soon see a huge chunk of future sales lost to home printing.

Promoting services and products under their own label will improve the innovation perception of a retailer’s brand, but this will not be sustainable in itself. For crowdsourced development and trialling, though, it should be a viable application in the long run.

Producers should try and co-operate with retailers to get their solutions and designs into stores. Retailers will be interested in providing innovative and personalised experiences instore so they ought to be open to approaches. Developing actual 3D printers that suit specific products as Hershey did or developing printable forms of products compatible with food printers now in development from XYZprinting will be important to prepare for a future where home printing is common and establish producers as material and design suppliers early on.

![]()